Kolliker’s Organ: A Baby Octopus’s Temporary Organ

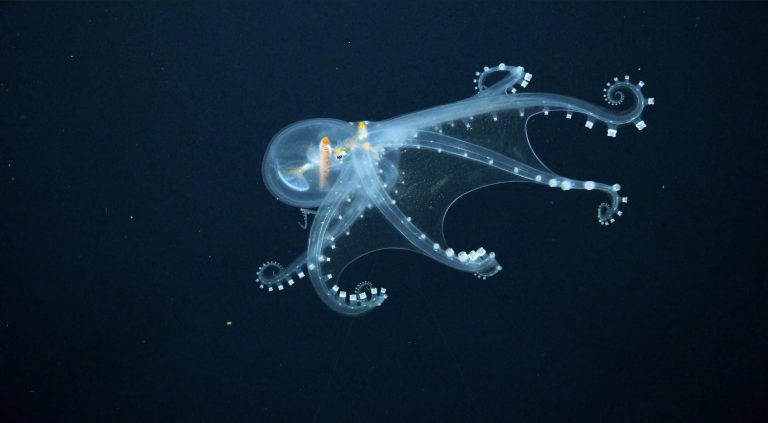

This just in! Another octopus secret has been unlocked! Baby octopuses are covered with tiny, microscopic structures known as Kolliker’s organs (KO) that help them sail the seas, make them appear larger than they really are, and aid in camouflage. Think of these organs as a biological guardian angel that protects them through their larval (baby) stage! While scientists have known about KO for nearly two centuries, recent studies are shedding more light on how this mysterious organ works and why it’s only found in the early years of an octopus’s life. Let’s find out more!

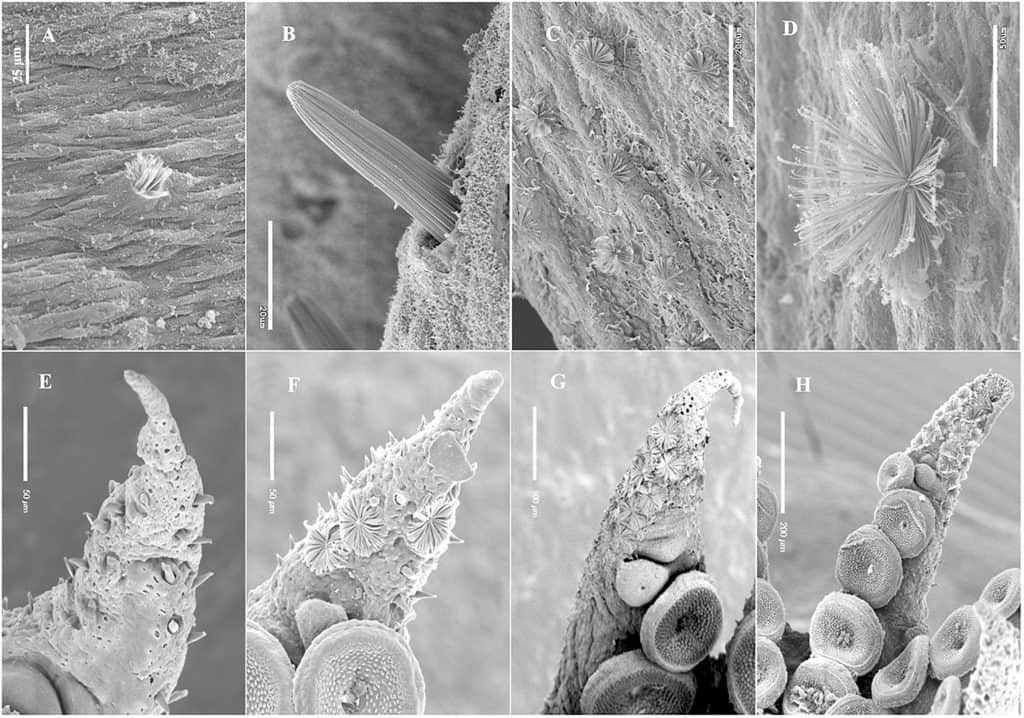

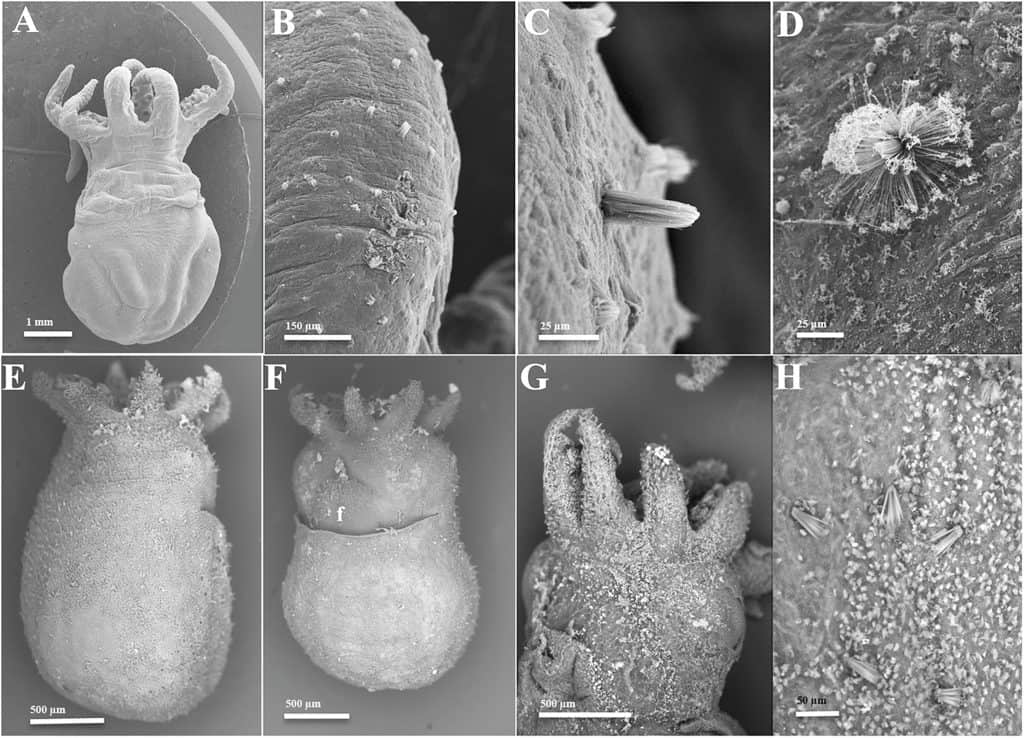

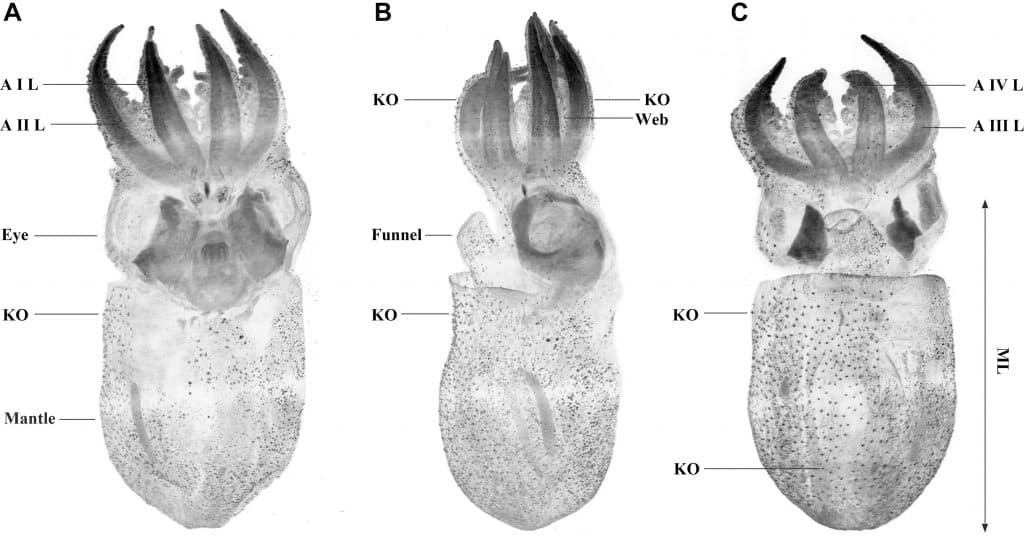

We’ve known for some time now that KO covers a hatchling’s body. They are temporary structures that look like a miniscule bristly broom that can open and close like an umbrella.

KO are around the same size and evenly distributed all over the skin of octopus embryos, hatchlings, and juveniles, but they are completely lost when they reach their sub-adult stage!

Are you wondering the same thing I am?

Why do they lose them when they reach maturity?

Do all octopuses have Kolliker’s organs?

Thankfully, a recent study published in May 2021, has unraveled some of these science mysteries! This study was able to shed some much-needed light on these questions about Kolliker’s organs.

How can you tell if an octopus has Kolliker’s organs?

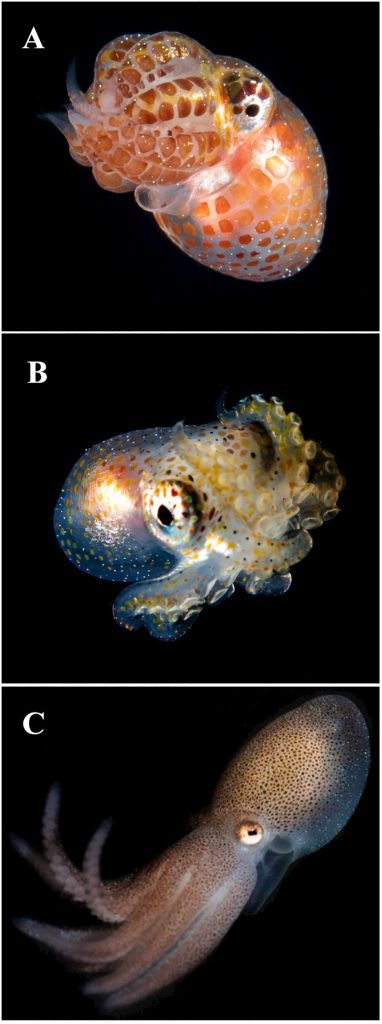

Researchers from across the globe, led by scientist Roger Villanueva, collected tissue from hatchlings and juveniles of 17 octopus species from different habitats.

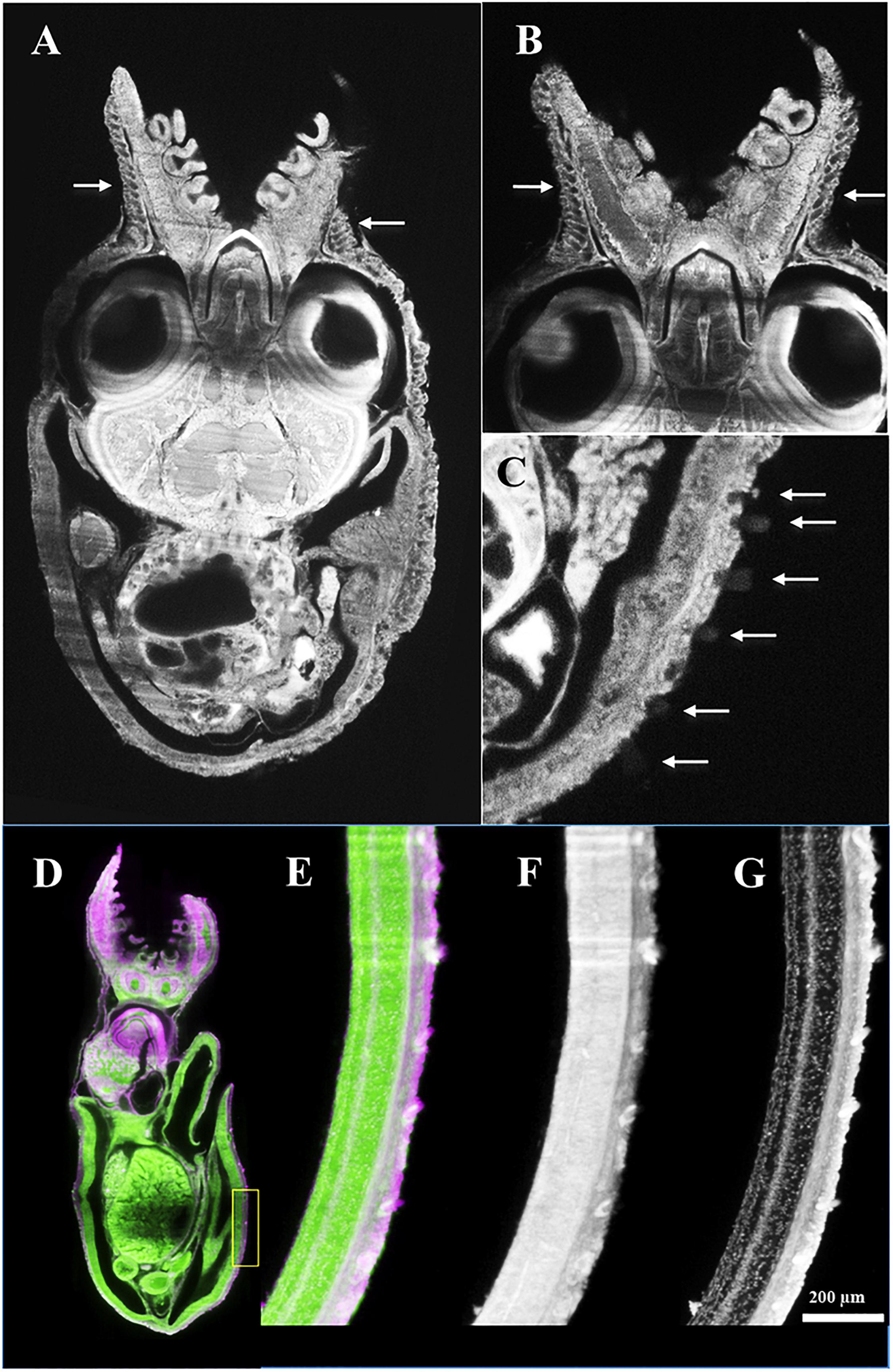

Since KO can’t be seen with the naked eye, the team at the Mesoscopic Imaging Facility in Barcelona used light-sheet microscopy to produce clear and detailed images of hatchling specimens.

This device and technique captures fine details in tissue samples and has the capacity to study large samples over extended periods of time without having to slice anything or only look at small sections like traditional microscopes.

What KO mysteries did this team of scientists with their super fancy, high-powered microscopes solve?

When Kolliker’s organs are spread wide open, they can increase an octopus’s size by 66%.

Having the ability to expand yourself could be quite useful when moving around the ocean. This study showed that baby octopus have fine control over their KO, only taking them a second to extend or retract them. They can even choose which ones to open or keep closed!

When opened, the KO can be flexed or rotated. Scientists think these organs potentially act like microscopic rudders helping them catch, or resist, ocean currents. This would allow them to conserve energy and help keep them afloat.

Imagine having tiny sails all over your body that you could open and close to body surf along the waves!

Did you know that Kolillker’s organs could play a role in camouflage?

While hatchlings come equipped with chromatophores, more camouflage options are always welcome. Especially when you’re a squishy little morsel in an ocean full of hungry fishes. They are no bigger than a grain of rice!

An earlier study from the 1970s found that KO can scatter light in all directions. This light refraction could make the hatchling appear fuzzy making it more difficult for a predator to catch them.

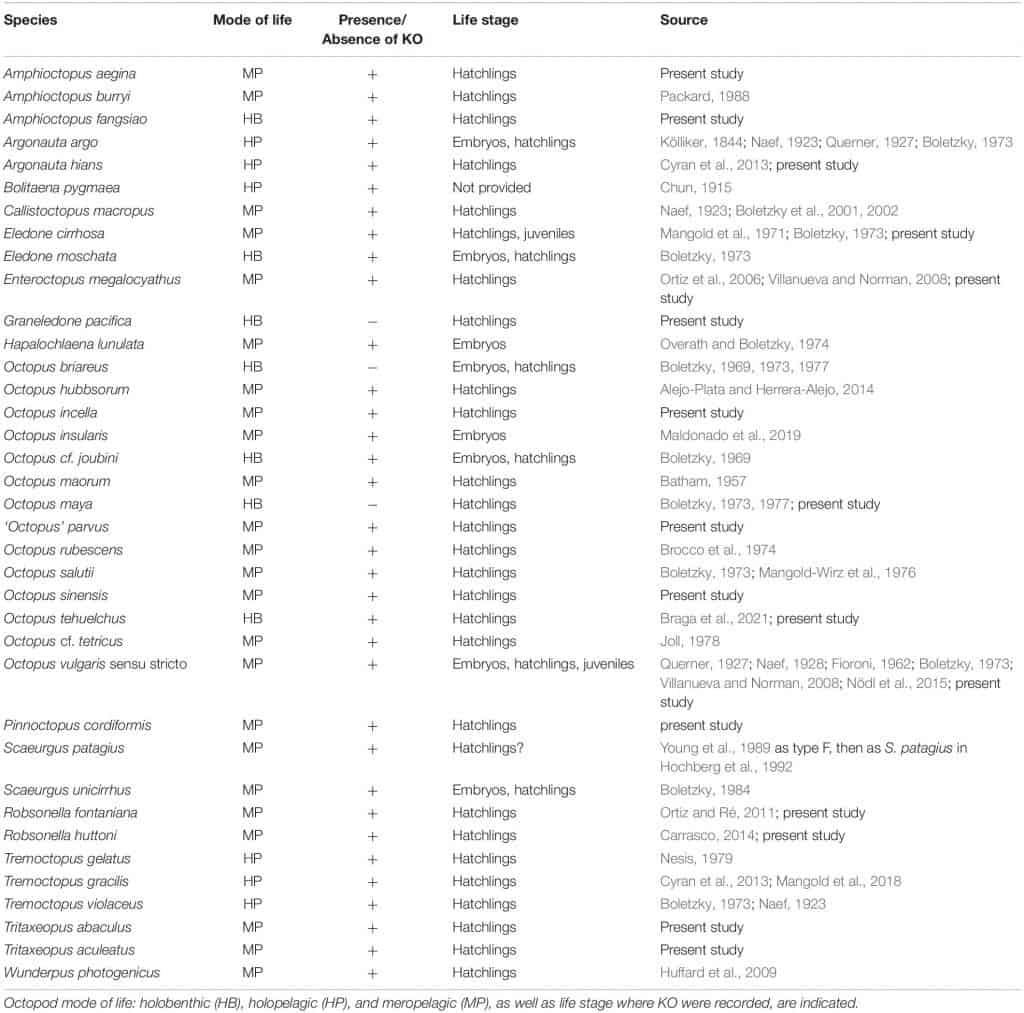

Do all baby octopuses have KO?

Another interesting knowledge nugget that came out of the 2021 study was that not all baby octopus have KO. Out of the 17 species collected, two had no KO at all!

For example- Our long brooding mama octopus, Graneledone boreopacifica, and the Mayan octopus (Octopus maya) are both a Deep Sea Octopus. Turns out an octopus’s life path has a lot to do with the presence, or lack thereof, Kolliker’s organs.

Let’s go back to the beginning!

When a baby octopus pops out of their egg and into the world, there are two predetermined paths they can take.

- Many octopus, like the Common Octopus (Octopus vulgaris), will lay upwards of thousands of small eggs with mama octopus caring for them for a few months. They hatch as miniature versions of a full-grown octopus and are called para-larvae. They are free-swimming and will spend their early days floating near the surface. That is till they’ve grown big enough to settle on a reef.

- Other octopus species take a different approach, like our Deep Sea mama, G. boreopacifica, who will care for her eggs longer (53 months!), ultimately producing larger eggs resulting in larger hatchlings who are quick to settle into the same habitat as their parents.

Since Deep Sea Octopus babies make their home on the reef shortly after hatching, they don’t need KO to help them fight ocean currents or keep them afloat.

Additionally, having their skin covered in tiny reflectors would also be pretty pointless when you live in a pitch-black environment with no sunlight to deflect.

Kolliker’s Organs: Do Baby Octopuses Need It To Survive?

While this study was the most in-depth look into KO that has ever been done, the researchers are convinced there are still mysteries to unlock when it comes to this fascinating organ.

Overall, it’s fun to think that baby octopus are out there surfing along ocean currents and confusing predators with refracted sunlight by just opening tiny bristly umbrellas all over their bodies.

Don’t you think? Let me know in the comments down below.

If you want to educate yourself some more about all sorts of different cephalopods, take a look at our encyclopedia. Or, what we call it, our Octopedia!

Connect with other octopus lovers via the OctoNation Facebook group, OctopusFanClub.com! Make sure to follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up to date with the conservation, education, and ongoing research of cephalopods.

More Posts To Read:

- Meet the Cockeyed Squid: the Deep-Sea Animal with a Giant Eye!

- 10 Facts About Baby Nautilus!

- Does Octlantis Exist?

- Dumbfounding Flapjack Octopus Facts You NEED To Know!

- What Is The World’s Biggest Octopus?

Corinne is a biologist with 10 years of experience in the fields of marine and wildlife biology. She has a Master’s degree in marine science from the University of Auckland and throughout her career has worked on multiple international marine conservation projects as an environmental consultant. She is an avid scuba diver, underwater photographer, and loves to share random facts about sea creatures with anyone who will listen. Based in Japan, Corinne currently works in medical research and scientific freelance writing!