When Do Senescent Octopuses Feel Pain?

🚨 New octopus research alert from marine scientist Meghan Holst and her team, who discovered and finally got an answer to the question: When do senescent (end of life) octopuses feel pain? This post reviews what happens when octopuses get older, delving into the senescence process, and most importantly, what implications this has for octopus well-being.

Remember how we felt when we realized “My Octopus Teacher” might be coming to an end? (won’t include spoilers just in case you haven’t seen it yet!)

The reality is that octopuses have relatively short lifespans that, on average, last 3-5 years (but can be as short as 6 months!). Crushing our hearts even further was finding out that a mama octopus stops eating after she reproduces and dies while protecting her eggs and or shortly after they hatch.

This process is known as senescence, and as sad as it may seem, it’s a normal part of an octopus’s life cycle. Both females and males go through this process shortly after mating.

The senescence stage

Senescence begins when…an octopus stops eating, leading to:

- Dramatic weight loss

- Becoming uncoordinated

- Gaining white lesions that don’t heal

- Eventually becoming dark grey or white

- Exhibiting corkscrew posture in their arms

While the outward indicators of senescence are well known, there is still a lot to learn about the processes going on INSIDE the octopus during this time.

What’s wrong, GPO?

Scientists have discovered that the reason octopuses stop eating has to do with a chemical secretion from the octopus’s optic gland, which is a small bean-shaped organ located between their eyes.

It’s similar to our pituitary gland at the base of our brain that tells other glands which hormones to release and helps regulate growth, blood pressure, and reproduction.

The mysteries surrounding the senescence process continue to garner the attention of cephalopod scientists around the world and lead us to Holst’s recent publication!

She set out to determine at what point in senescence an octopus begins to feel pain.

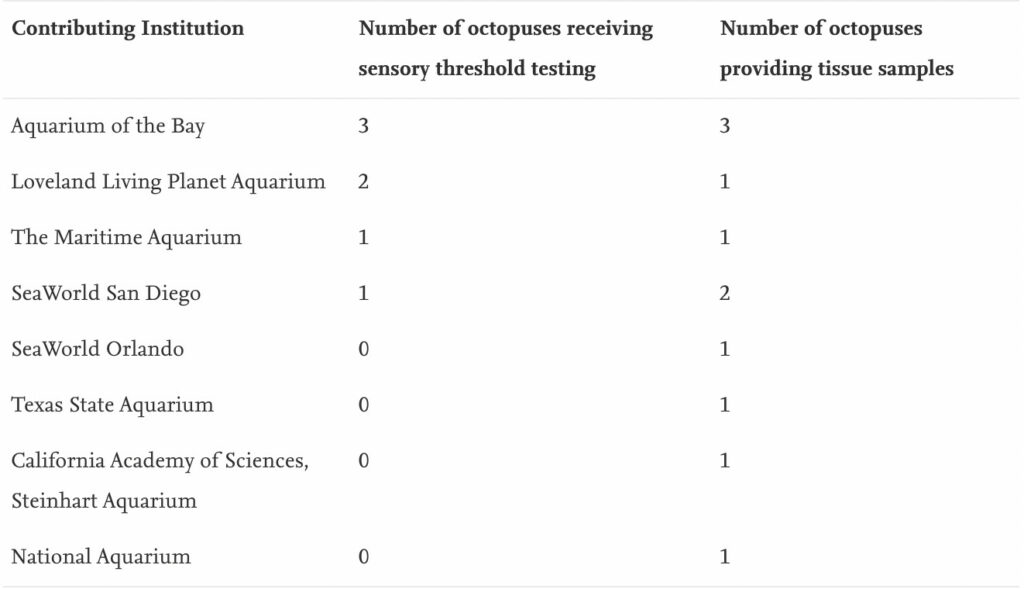

For her study subject, she chose the Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), also known as the GPO. Eleven GPOs from 8 U.S. Aquariums were a part of this study to determine at what point in senescence an octopus begins to feel pain.

How do researchers figure out if an octopus feels pain?

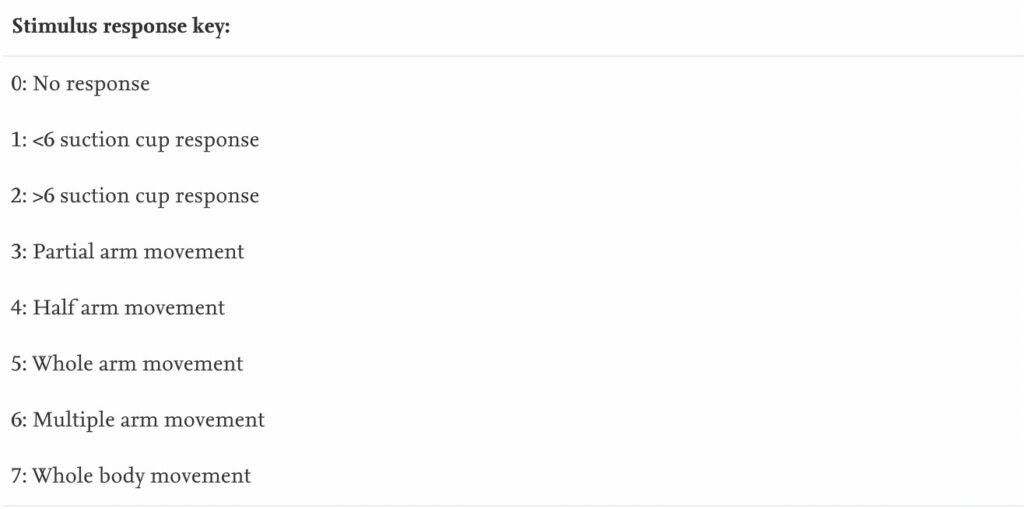

To test sensory responsiveness, scientists and octopus caretakers touched octopuses on their mantle, arm base, and arm tip with a very light filaments (thread-like fibers made from nylon) used for touch test sensory. (note: this tool does not hurt the octopus, it’s super bendy!)

They did this weekly, and their reactions were recorded over the course of senescence.

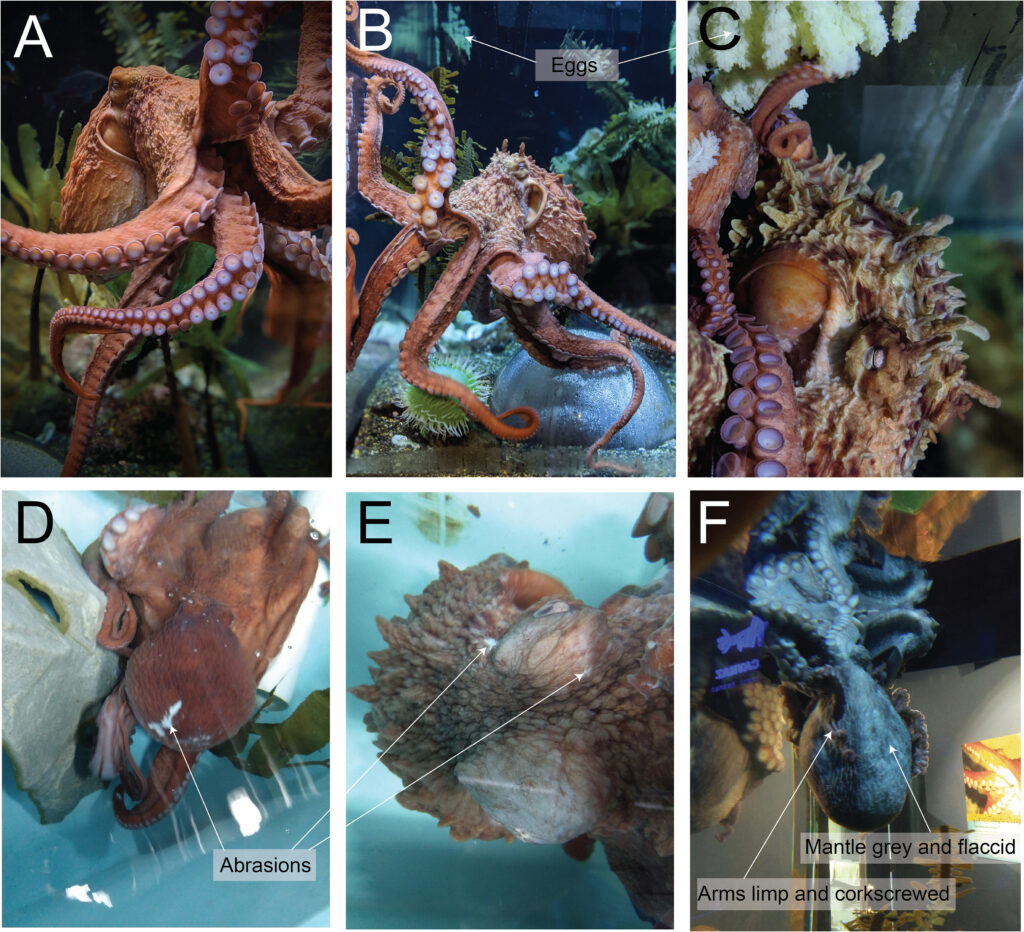

A. A healthy, pre-reproductive female.

B &C. A female in the early stages of post-reproductive senescence. Eggs are visible in the enclosure, but the animal is still in excellent outward condition and showing largely normal behavior.

D&E. Images of an animal mid-to-late senescence. The skin is beginning to lose muscle tone and color, and there are accumulating, unhealed wounds on various bodily regions.

F. A terminally senescent, perimortem animal showing overall pale coloration, skin laxity, limpness, and distal corkscrewing of the arms.

By: Meghan Holst

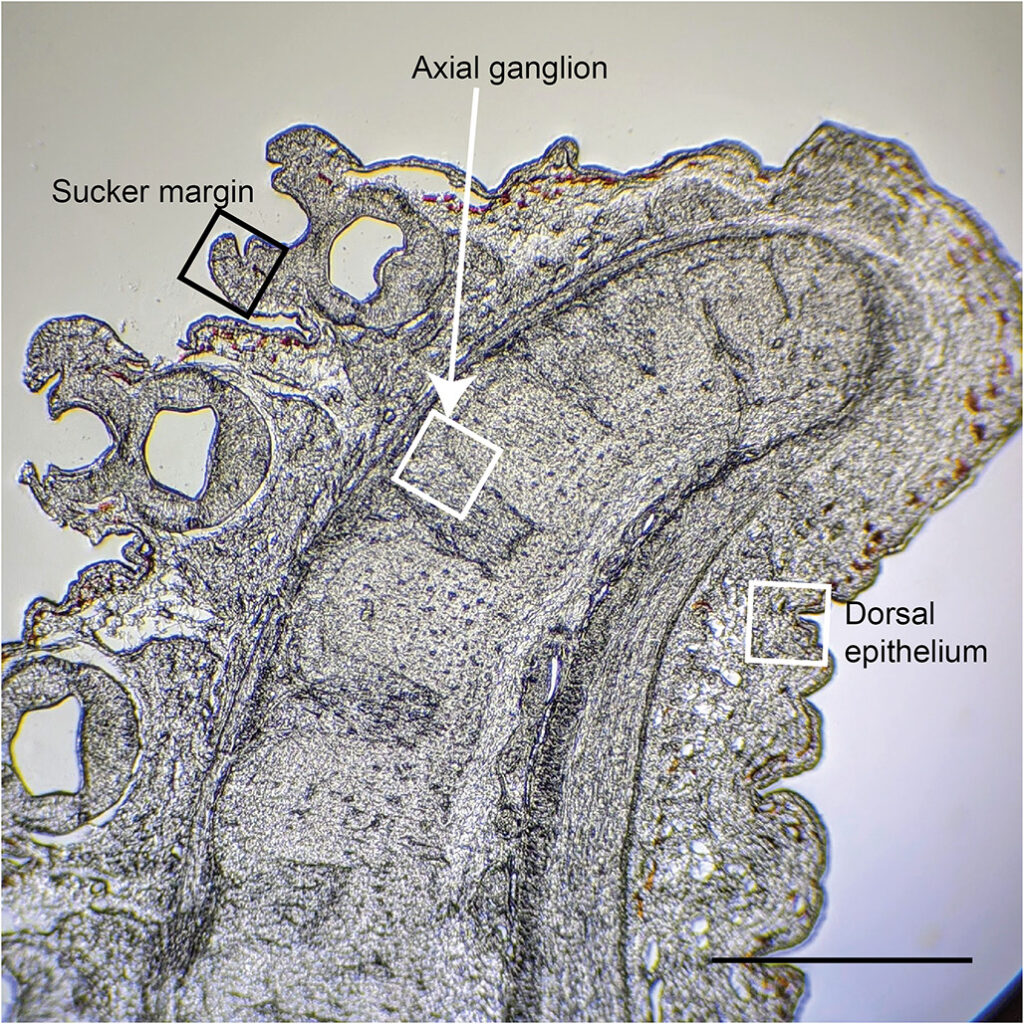

After senescence, Holst collected the arm tips to examine the cell densities under the microscope to help explain their reactions (or lack thereof) to the filaments during different stages in senescence.

🐙 Octopus Fun Fact

If you really want to nerd out, check out her IG @megholst for the cool (literally!) way she prepared her arm tip samples.

When do senescent octopuses feel pain?

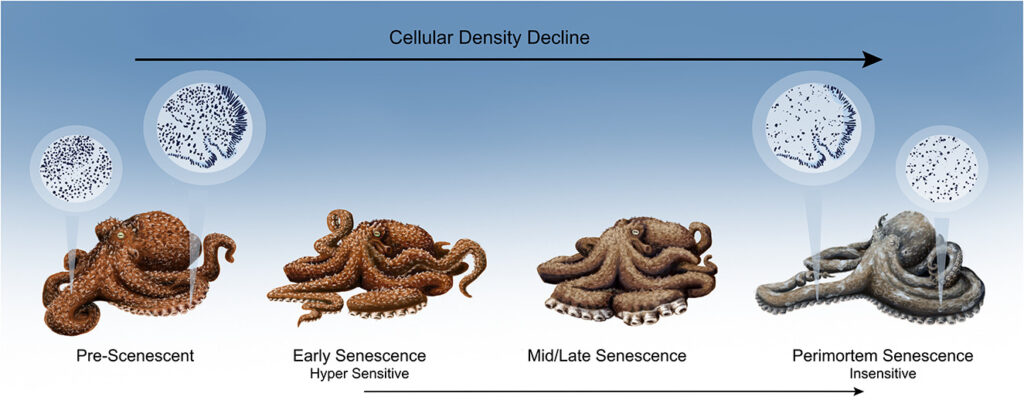

“What surprised me the most was that octopus display hypersensitivity at the beginning of senescence.” Holst describes, “This isn’t what I expected at all!”

Turns out that octopuses in the EARLY stages of senescence were very sensitive to being poked. This is while the octopus looks healthy before any of the outward signs of senescence are even visible. Further examination of the preserved arm tips showed a clear decrease in cell density as the GPO approaches the end of its life.

“I thought sensitivity would correlate with physical decline, becoming more sensitive as they near death,” Holst explains. “Instead, we saw them become hypersensitive right at the beginning of senescence, sometimes before they even deposited gametes [sperm and eggs]. By the time they neared death, they were almost completely unresponsive.”

So, why is any of this information important?

If you’re reading this, it’s safe to assume you love octopuses, possibly bordering on having a slight obsession with them (we get it)!

Since we care deeply about these cephalopods, it’s important to know they are treated well while housed in aquariums, zoos, or in a research lab setting.

How are octopuses taken care of in aquariums?

There are the basics, which are to provide them with:

- Food

- A proper tank set up with a steady supply of highly oxygenated saltwater

- Good filtration

A step further is to make sure their emotional and mental well-being is taken care of.

As we know, octopuses are incredibly intelligent beings, so providing them with mental stimulation in the form of toys and puzzles, including live food to chase down, will help to alleviate any octopus boredom.

Bored octopuses tend to become little Houdini’s, and next thing you know, you have an octopus on the loose!

Let’s say the basic needs AND health boxes are all being checked…

What about when an octopus comes to the end of his or her life?

Knowing HOW and WHEN an octopus feels pain allows us to provide better care for them.

Currently, invertebrates in the USA are not included in the federal regulations that govern animal welfare. However, across the pond, the U.K. amended their Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill to include cephalopods and decapods after researchers gathered over 300 scientific papers determining that they are sentient beings with the capacity to experience pain.

This means that any research being done on octopuses follows the same rules and regulations as are followed for studies done on vertebrates.

We need more octopus studies!

Holst’s study, and more studies like this in the future, are imperative in aiding and hopefully improving octopus welfare so we can provide them with the best possible care while in captivity.

Even with this new research out, Holst still has questions she wants to answer.

“Future research that would support our learning about octopus senescence would be to evaluate if stimulation is reaching the central nervous system as they near death. Are the nerves still transmitting stimulus signals from the peripheral nervous system (through the arms) to the central nervous system (main brain of octopus) at the end of their reproductive period?”

Holst muses, “This is a question we weren’t able to answer in this study that I definitely want to know.”

Knowing GPO feel pain early on in the reproductive phase can help us provide better care in the form of not handling them unnecessarily and improving the time frame of their lifespan.

We are excited to help make a change in an octopus’s life

Holst is excited about future studies in this area of cephalopod research, saying:

“I am very encouraged and excited to see the research coming out, particularly from Dr. Robyn Cook’s lab at San Francisco State University. I believe the more we learn, the better we will be at interpreting octopus welfare, and we are well on our way to doing so. Improving the science that supports our ethical standards is a great step towards ensuring the welfare of octopus as we do with vertebrate species.”

Now that we know when senescent octopuses feel pain, hopefully, this will lead to a happier and healthier world for octopuses in aquariums.

🐙 Octopus Fun Fact

Warren and Meghan did a fun virtual visit at Aquarium Of The Bay where we got to meet Octavia, the Giant Pacific Octopus!

If you want to educate yourself some more about all sorts of different cephalopods, take a look at our encyclopedia. Or, what we call it, our Octopedia!

Connect with other octopus lovers via the OctoNation Facebook group, OctopusFanClub.com! Make sure to follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up to date with the conservation, education, and ongoing research of cephalopods.

More New Posts To Read:

- Which Direction Is The Front Of An Octopus?

- Do Octopus Have Beaks?

- Do Octopus Have Bones?

- Everything You Need To Know About An Octopus Brain!

- How Many Hearts Does An Octopus Have?

Corinne is a biologist with 10 years of experience in the fields of marine and wildlife biology. She has a Master’s degree in marine science from the University of Auckland and throughout her career has worked on multiple international marine conservation projects as an environmental consultant. She is an avid scuba diver, underwater photographer, and loves to share random facts about sea creatures with anyone who will listen. Based in Japan, Corinne currently works in medical research and scientific freelance writing!