“Sperm Worms”: How Male Argonauts Taught Scientists About Octopus Sex

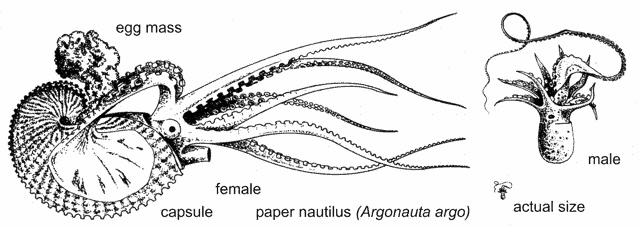

Argonaut octopuses are best known for what appears to be a beautiful, delicate spiral shell. We now know that female argonauts spend their whole lives growing these thin ‘shells’, which they use as buoyant submersibles and as brood chambers for their eggs. But what about male Argonauts? For hundreds of years, no one ever saw them or even knew if they existed! Let’s talk about em’!

The Lady, the Octopus, and the Aquarium

In the 19th century, french marine biologist Jeanne Villepreux-Power twigged on to the idea that certain “parasitic worms” might actually be the males of the species. A series of surprising revelations eventually led to a more complete understanding of not only Argonaut sex but all octopus sex.

When Jeanne Villepreux-Power began to study octopuses in the 1830s, people were still arguing over whether female Argonauts made their own shells or stole them, as hermit crabs do!

To solve the debate, Jeanne invented aquariums that let her keep argonauts alive while she observed and experimented on them. Yes, actual aquariums!

She proved that the females do indeed make their own shells, beginning right after birth. But Jeanne, like researchers before her, couldn’t find argonaut males.

With this mystery in mind, she became interested in a type of parasitic worm often found in the shells of female Argonauts while they were brooding eggs.

“Hundred-cupped thing from an octopus”

These worms had recently been given the scientific name Hectocotylus octopodis by the widely-respected scientist Georges Cuvier.

Cuvier worked at the French Academy of Sciences and was famous throughout Europe for his ability to identify any bone or fossil and for his paradigm-shifting theory of extinction. His contributions to paleontology and biology helped shape the fields as we know them today; however, in the case of Hectocotylus, he was quite wrong.

The Latin name means “hundred-cupped thing from an octopus” and refers to the suckers lining the worm’s body–which Jeanne correctly identified as octopus suckers.

The “worms,” in fact, looked so much like octopus arms that she wondered if they could be a kind of octopus. When dissected, they always contained sperm, so perhaps they were male Argonauts, much reduced in size compared to the females!

Are male Argonauts worm-shaped?

Because the “worms” had been described as whole organisms, Jeanne expected to see them as such, even when she began to consider the possibility that they might be a kind of octopus.

She thought that she saw a mouth and a digestive tract on each hectocotylus (male octopuses’ “special” arm). This kind of mistake, believing that we see what we expect to see, is a common one for humans to make, and scientists are, of course, humans.

We all have biases influencing our perceptions, tempting us to interpret ambiguous findings in favor of our pet theories. In the nearly two centuries since Jeanne’s research, scientists have developed and standardized many techniques (such as double-blind studies) that help avoid these perceptual pitfalls.

We’re still working on a more thorough adoption of these techniques, as well as more careful use of statistics and peer review.

The boys with the detachable arms

Despite her mistaken identification of the hectocotylus “worm” as a whole octopus, Jeanne did something that remains extremely important in science today: she published her theory. This brought it to the attention of other scientists, encouraging them to look at the hectocotylus more closely so that Jeanne’s idea could be refined and corrected.

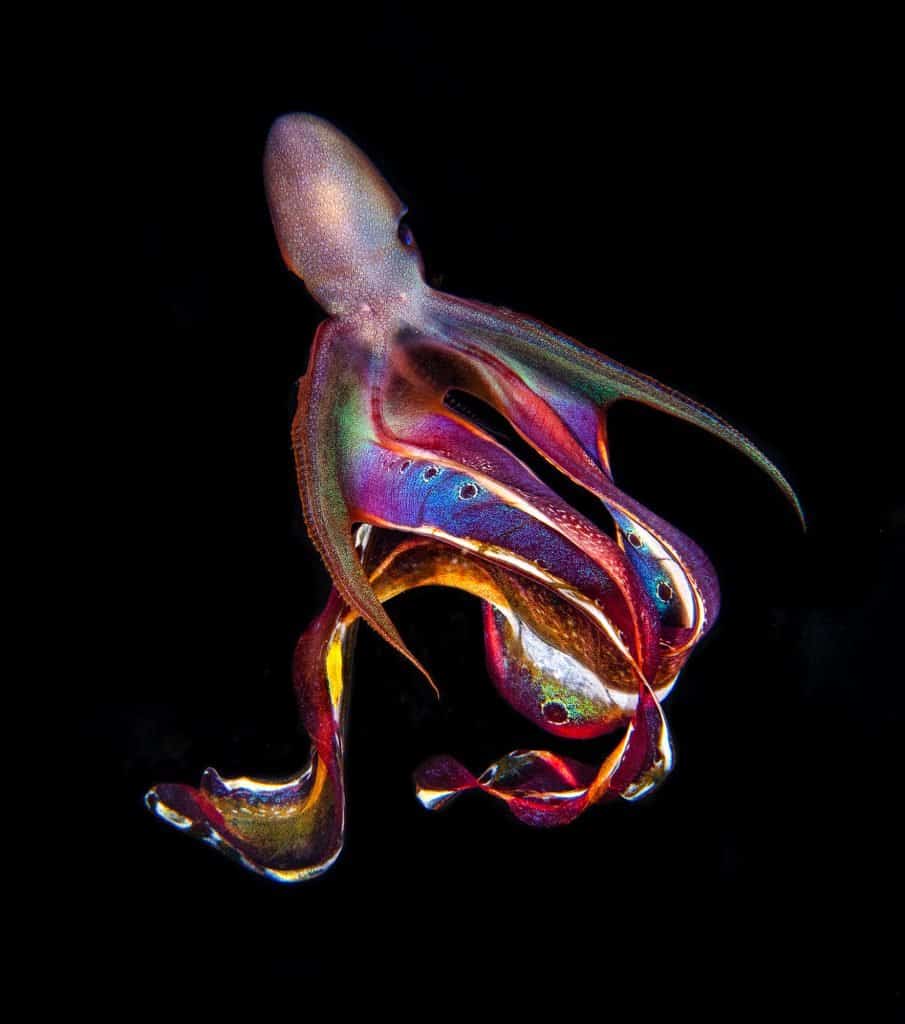

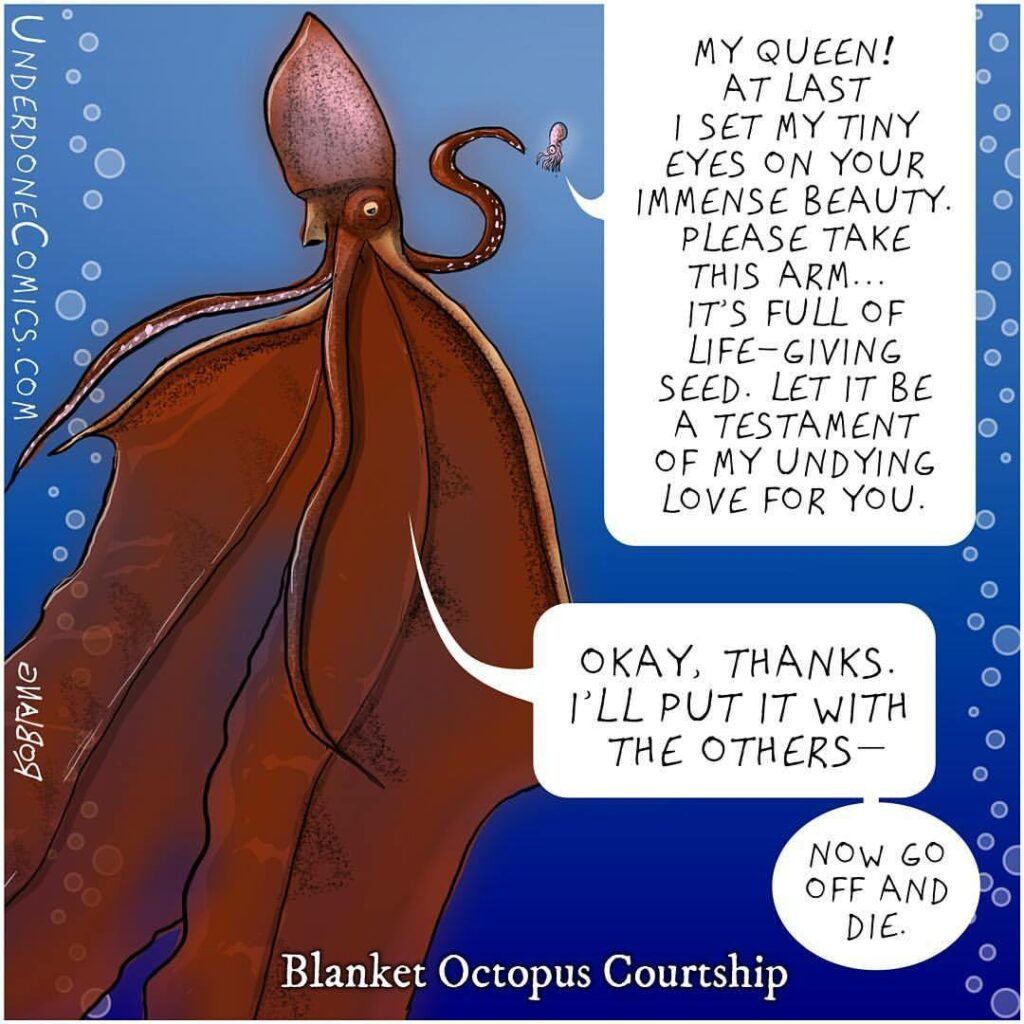

In the 1840s, a scientist named Albert von Kölliker examined hectocotyli (the plural of hectocotylus) that he found associated with females of both Argonauts and closely related Blanket Octopuses.

Overall, he agreed with Jeanne’s theory, but the hectocotyli seemed strangely minimalist to him: he could not find any “organs of sight or hearing” nor any “anal orifice.”

Shortly afterward, a different researcher named Heinrich Müller finally discovered small whole octopuses–complete with eyes and anuses–bearing an enlarged arm that looked exactly like a hectocotylus.

While the other seven arms of these little guys were proportional to their small size, this arm was several times longer than the rest of the male’s body and would “drop off on being touched.”

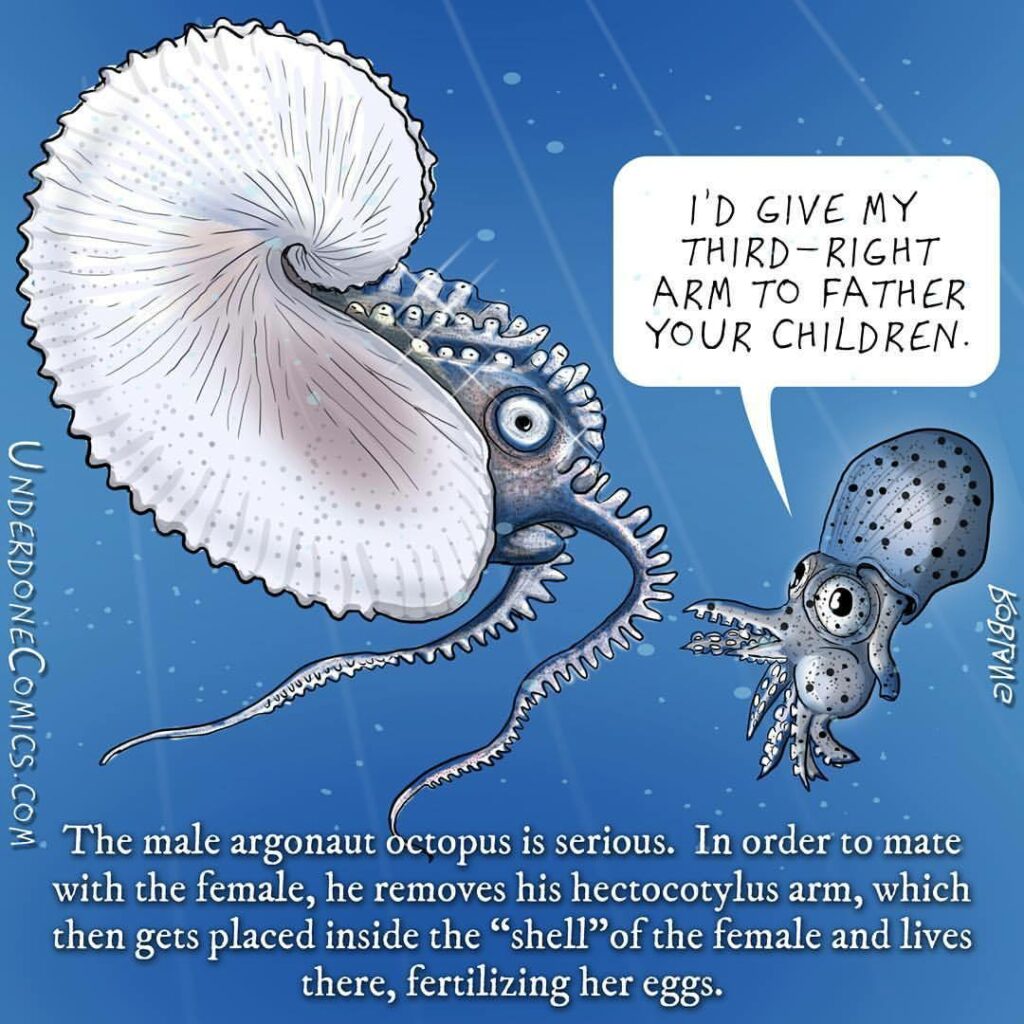

The hectocotyli that had once been considered parasitic worms were actually the detached arms of male Argonauts!

“The name ‘Hectocotylus’ may very well be retained,” Müller wrote, “without any implication of independent animality.”

A New View of Octopus Sex

So hectocotylus became the anatomical term for the sperm-bearing arm of a male Argonaut.

And once that was sorted out, scientists pretty quickly began using it for the arms of other male octopuses (and squid and cuttlefish) that are modified for sperm delivery.

Octopus sex, it turns out, usually involves a special male arm. Although, in most species, this arm is only subtly different from the other seven. It has a narrow groove and a modified tip for delivering sperm packages into the body of the female.

Mating at arm’s length is advantageous for octopus males, who might otherwise get eaten by their mates! The detachable arm of Argonauts and Blanket Octopuses may have evolved as even more drastic protection.

“Remote mating” allows delivery of sperm from beyond eating distance. However, this theory has a major flaw: as far as we know, male Argonauts cannot regrow a new hectocotylus.

They only get one shot at reproduction and probably don’t live much past that moment of truth.

A Terminal Amputation

Both males and females of some other octopus species can deliberately drop arms for defensive purposes, like a lizard dropping its tail when pursued by a hungry cat. This process is called autotomy, or “self-breaking”. It’s facilitated by an area of the arm that’s predisposed to breakage, like perforations in a roll of paper towels.

The octopus loses the arm, escapes the predator, then grows it back. Whereas autotomy of non-reproductive arms in other octopus species is typically followed by regeneration, we have no evidence that male Argonauts (or their relatives) can regrow the hectocotylus once it is given away.

That’s probably because it’s a much larger investment of energy, both in its sheer size and in the quantity of sperm it contains. Males simply don’t have the resources to grow more than one.

Such “terminal breeding” is common in octopuses, but in most species, it’s the female who uses up all her resources on a single batch of eggs, starving herself as she broods her babies.

Argonauts reverse that typical octopus narrative, with females that brood a new batch of eggs each season, collecting hectocotyli from male after doomed male.

Special thanks to Danna Staaf!

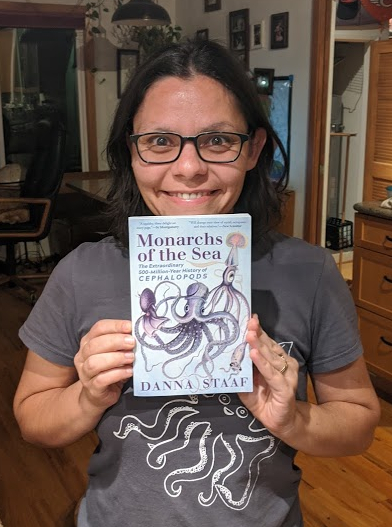

Thank you to Danna for sharing her knowledge about argonauts, the magnificent octopus hitchhikers grabbing rides on jellyfish & other fun things!

Danna Staaf is a cephalopod scientist and author, with a new argonaut-focused book coming in October. The Lady and the Octopus: How Jeanne Villepreux-Power Invented Aquariums and Revolutionized Marine Biology is now available for preorder, and Staaf will be sharing more wild and wacky argonaut stories with OctoNation in the months to come!

If you want to educate yourself some more about all sorts of different cephalopods, take a look at our encyclopedia. Or, what we call it, our Octopedia!

Connect with other octopus lovers via the OctoNation Facebook group, OctopusFanClub.com! Make sure to follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up to date with the conservation, education, and ongoing research of cephalopods.