How An Argonaut Shell Is Spun Out Of Their Arms

Part 3 of our series on all things Argonauts! Danna Staaf is back to share some more of her extensive knowledge of Paper Nautilus. So far, we have learned that Argonauts like to hitch a ride on a jellyfish and how male Argonauts taught scientists all about octopus sex. Today, Danna is going to teach us all about the Argonaut shell! Is it true – do they make their own shells? Let’s find out.

Have you ever collected seashells? Beaches and curio shops are packed with variety: shell colors from sunset pastels to bold stripes; shell shapes from plates to weapons to musical instruments.

Most seashells are made by mollusks, a group of animals that includes:

- Clams

- Snails

- Oysters

- Abalone

- Nautiluses

- And, of course, octopuses! and many others.

All mollusks have a “main body” called the mantle, which contains their organs. Not all mollusks have shells, but those that do produce their shells with their mantles.

There is only one exception: the Argonaut Octopus and its delicate spiral shell.

Meet the octopus “sailors”

The octopus that we now call an argonaut was well-known around the Mediterranean in antiquity and was at first named Nautilus. “Nautilus” is a form of the ancient Greek word for “sailor.” These animals were called sailors because their shells look like boats, and two of their arms have large membranes that look like sails.

In fact, artists typically illustrated them floating on the sea surface, spreading their “sails” to catch the wind. But it was fantasy–real octopuses don’t do that!

During the Age of Discovery, Europeans began to learn about animals in other parts of the world. They saw shells from the Indo-Pacific shaped like their familiar “nautilus” shells, but thicker and made with mother-of-pearl. Furthermore, these new shells had internal chambers.

The Indo-Pacific shells became known as “Pearly Nautiluses” or “Chambered Nautiluses,” while the Mediterranean shells were rebranded “Paper Nautiluses” to emphasize their pallor and fragility.

I say these names were given to the shells because often it was only empty shells that European naturalists observed and classified. But, all those shells had once been occupied, and typically people referred to the living occupants by the same names (Pearly Nautilus or Paper Nautilus).

🐙 Octopus Fun Fact

In 1758, the Paper Nautilus acquired a Latin name: Argonauta argo. “Argonaut” also means “sailor”–specifically, a sailor on the mythical ship Argo, sometimes described as the Mediterranean’s very first ship.

Scientists began to call Paper Nautiluses Argonauts, and this usage grew more popular until now “nautilus” is used primarily for Pearly Nautiluses.

Creators or thieves?

People knew that argonauts were different from other mollusks because they could crawl in and out of their shells. By contrast, the only way to remove a snail from its shell is to tear its body, which kills the animal. This holds true for all other mollusks, from clams to nautiluses. The shell remains glued to the mantle that grows it.

Argonauts, however, are attached to their shells merely by the strength of their arm muscles and suction cups. They can release their hold at any time–more like hermit crabs than like snails.

This led some scientists to suggest that argonauts must get their shells as hermit crabs do: by stealing. A hermit crab cannot grow its own shell; it must hunt for an empty mollusk shell. (Or, in modern times, an empty can or plastic bottle.)

But no one had ever seen a mollusk other than an Argonaut inside an Argonaut shell, so who could be making these distinctive shells, if not the Argonauts themselves? The argument went back and forth.

“I perceived that lack of experience was the cause of these different opinions,” wrote marine biologist Jeanne Villepreux-Power in 1856. She was tired of scientists speculating on empty shells rather than experimenting on live animals. “Everything should be cleared up if one conducted thorough research on this interesting point.”

A pioneering woman in science

Jeanne Villepreux-Power grew up in rural France, far from the ocean. Adventurous and inquisitive, at age seventeen she traveled on foot to Paris, where she made a name for herself as a talented seamstress. Through her work, she met a wealthy merchant who lived in Sicily, and eventually, she married and moved in with him. She was captivated by the Italian island’s natural beauty and began to investigate the rich biological diversity of the surrounding sea.

Perhaps because she was an outsider, a woman at a time when science was dominated by men, and self-taught rather than formally educated, she took a novel approach to the Argonaut puzzle.

To find out if they made their own shells, Jeanne invented several ingenious contraptions to keep argonauts alive and healthy for observation and experimentation. These included the first glass aquariums, as well as wooden enclosures installed in the sea itself.

Male and Female Argonaut Paper Nautilus inside salp By: Scott Gutsy Tuason of Squires Sports

Protected from predators and fed fresh seafood collected by Jeanne herself, the argonauts demonstrated their abilities.

Adults could not create an entirely new shell if separated from their old one, but they could mend broken shells by secreting new shell material from their sail-like arms.

Babies did not grow shells in the egg, but within hours of hatching their tiny arm membranes began to produce the shell they would continue to grow throughout their lives.

The mystery was solved: Argonauts make their own shells, and they do it using not their mantles, but their arms.

Unique mother mollusks

Scientists do not consider the Argonaut shell a “true” shell. A true shell is secreted by the molluscan mantle, which gives it a specific chemical composition.

Both argonaut shells and true shells are built from calcium and proteins, but the proteins are entirely different. An argonaut shell also lacks the calcium composite called aragonite that can build mother-of-pearl in the pearly nautilus and other mollusks.

Argonauts, like all octopuses, evolved from distant ancestors that did grow shells with their mantles. But octopus ancestors lost this ability as they developed malleable bodies that could squeeze through tight spaces and camouflage with any background.

Early seafloor-dwelling octopuses also evolved the behavior of laying eggs in dens. They could make dens in rocky crevices, sandy burrows, or empty clam shells. (Yes, some octopuses do behave like hermit crabs, after all!)

Then, some of these octopuses evolved a peripatetic habit. Instead of crawling on sand or rock, they swam through the open ocean, so when females were ready to lay eggs, there were no dens in sight. These octopuses became the argonauts.

We don’t know which happened first, argonauts becoming open-ocean swimmers or argonauts beginning to secrete shells with their arms, but the two behaviors went hand in hand (or arm in arm, or sucker in sucker). Thus, a modern argonaut mother can create and carry a mobile den for eggs.

Other mollusk shells protect their inhabitants from predators. Argonaut shells, by contrast, are built not as armor but as a nursery. Rather than “shells,” scientists call them calcified egg cases.

Still, a “calcified egg case” can make a gorgeous addition to a seashell collection.

Special thanks to Danna Staaf!

Thank you to Danna for sharing her knowledge about argonauts, the magnificent octopus hitchhikers grabbing rides on jellyfish, and teaching scientists about octopus sex!

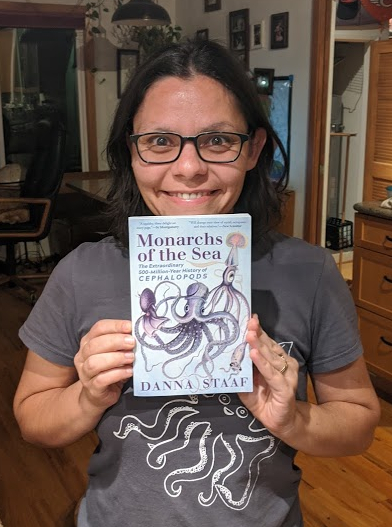

Danna Staaf is a cephalopod scientist and author who just published an argonaut-filled book for young readers: The Lady and the Octopus: How Jeanne Villepreux-Power Invented Aquariums and Revolutionized Marine Biology. Danna has loved writing this argonaut blog series for OctoNation, and looks forward to many more collaborations!

Buy a copy now! 👇

If you want to educate yourself some more about all sorts of different cephalopods, take a look at our encyclopedia. Or, what we call it, our Octopedia!

Connect with other octopus lovers via the OctoNation Facebook group, OctopusFanClub.com! Make sure to follow us on Facebook and Instagram to keep up to date with the conservation, education, and ongoing research of cephalopods.

References:

- Etymology of nautilus: https://www.etymonline.com/word/nautilus

- How mollusks make shells with their mantles: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-are-seashells-created/

- Jeanne’s original research on argonauts (in French): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/exp7jq6q/items

- Recent research on the structure and formation of argonaut shells: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4352/10/9/839/pdf